Note: This article was originally published in the January 2013 edition of The Advocate, a publication of the Idaho State Bar. While specific quotes from letters of defendants are used in the article, they are used as examples to illustrate deficiencies with the public defender system, not individual performance of public defenders who are often overburden with the inadequacies of a broken system.

---------------------------

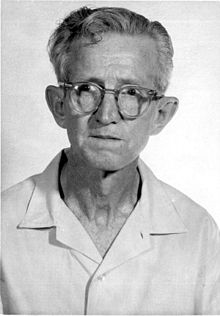

Shortly before lunch fifty years ago, on January 15, 1963, Chief Justice Earl Warren called up case number 155, then known as Gideon v. Cochran, and recognized the accomplished D.C. lawyer Abe Fortas to begin his argument at the podium. The Supreme Court had appointed Fortas (who would ascend to the Supreme Court bench two years later) to represent the prisoner and convicted felon who had sent the Court a handwritten petition for a writ of certiorari. The only question for the Court was whether to overrule long-established precedent: its 1942 holding in Betts v. Brady that state courts had no federal constitutional obligation to appoint counsel for people accused of a felony but too poor to hire an attorney. Two months after argument, on March 18, 1963, the Court announced its decision that “lawyers in criminal courts are necessities, not luxuries.” Ever since, each state has been on notice that the U.S. constitution requires a statewide system for ensuring that all criminal defendants, even the poor ones, have a lawyer to assist them. Without a working system, our “noble ideal” of “fair trials before impartial tribunals in which every defendant stands equal before the law,” as the unanimous Supreme Court said, is instead an impossible promise.

The Status Quo in Idaho: Underfunded, Inconsistent, and Unconstitutional Indigent Defense

Gideon himself was kept locked up in the Raiford State Prison for the whole duration of his U.S. Supreme Court appeal. It was not until two years after his 1961 conviction for breaking and entering a pool hall that he got a new trial. After the second trial on August 5, 1963, represented by an able lawyer this time, it took the jury only an hour to acquit. When a state’s indigent defense system is not working, there is more at stake than an abstract ideal, or a risk management concern about exposing the county treasury to liability. Rather, as Clarence Gideon’s plight reminds us, human dreams and liberty are on the line.

Recently, Idaho’s governor-appointed Criminal Justice Commission authorized the National Legal Aid and Defender Association (NLADA) to evaluate trial-level public defender services in our state. The results were clear and grim: the study found that the State of Idaho fails to provide the level of representation required by the Constitution. In excruciating detail over more than 100 pages, the report itemizes glaring deficiencies in Idaho’s system, taking in turn the excessive workloads that Idaho’s public defenders struggle under, the cattle-car proceedings in magistrate courts where defendants are pressured to “work out a deal” before getting appointed counsel, and the pervasive lack of training and supervision for public defense attorneys throughout the state. In other words, Idaho’s public defenders are not bad lawyers—they’ve simply been given the impossible task of representing too many clients with too few resources.

Although the additional cost to all of us of resulting post-conviction reversals may alone be compelling enough to demand an overhaul, the experiences of Idahoans across our state reveal the system’s devastating human consequences. One citizen wrote:

“my public defender does not like me because I’m deaf; at one point he started [to] swing his hand back and forth in front of my face (as if slapping my face) telling me to shut up because I would not take a plea deal”

His report came in a letter from Payette, Idaho. A man in Rexburg reported, exasperated, that

“for 10 months I have not had any preparation or actions taken on my case except continuations”

He wrote from the Madison County jail. A prisoner in the Ada County jail gave this report:

“He told me that my witnesses were not being cooperative and that I was going to trial by myself. I weighed my options and decided to plead guilty. I called my wife and found out that my witnesses were called by my attorney and told not to come to court the following day. My public defender withheld information from me. He did not let me know that I had witnesses in my defense, which persuaded me to plead guilty. I was basically misled into pleading guilty.”

A disturbing number of prisoner letters contain reports like these:

“[my public defender] coerced me into pleading guilty by stating that because I’m black and the alleged victim is white, I needed to plead guilty and take a deal because here in Idaho nobody would believe me”

“At my hearing, [my public defender] made the statement to me that I was not going to win my case because I was ‘just another f[--]kin Mexican walking in Northern Idaho’”

Unfortunately, in Idaho there is no way to comprehensively treat these symptoms. At present, aside from providing a statutory basis for appointment of counsel for the indigent, the State of Idaho has not taken responsibility for complying with Gideon v. Wainwright at the trial level. Instead, it has for decades relied entirely on the counties to develop 44 of their own systems for assuring that indigent accused are receiving meaningful assistance of counsel. This county-by-county approach has failed. As the NLADA Report explains, “[b]y delegating to each county the responsibility to provide counsel at the trial level without any state funding or oversight, Idaho has sewn a patchwork quilt of underfunded, inconsistent systems that vary greatly in defining who qualifies for services and in the level of competency of the services rendered.”

2013 is the Year to Fix Our Broken System

Providently, the three 50-year anniversaries of Gideon during 2013—the January 15 oral argument, the March 18 decision, and the August 5 acquittal achieved by appointed counsel—could mark milestones for overdue reform to Idaho’s public defense system. The Idaho Criminal Justice Commission recently voted to recommend changes to Idaho’s appointed counsel statutes and the creation of a committee within the Idaho legislature to develop a proposal for system-wide reform. The state’s move to look seriously at reform follows our neighbors—Oregon, Washington, Nevada, Montana, and Wyoming—which have already implemented state-level oversight mechanisms. And if an Idaho legislative committee takes this issue up during 2013, it will be considering it at the same time that impact litigation, aimed at ending constitutionally inadequate public defense systems, continues to move ominously through the courts in other states.

In addition to state-level attention to these problems, the Commissioners in Canyon County, where the NLADA Report noted a “continuing devolution” of the right to counsel in the face of “the move to place cost concerns above constitutional due process,” recently had the courage to candidly admit their own “grave concerns” about the indigent defense system there. The Canyon County Commissioners also questioned “the very constitutionality of the State of Idaho delegating its responsibility—by unfunded mandate—to the counties . . . .” Accordingly, Canyon County has already begun exploring the development of a model system of public defense, with the goal of implementing it by 2014.

Canyon County has a wealth of national research and standards to guide it. In particular, the Commissioners have expressed interest in building the framework of their model system from the Ten Principles of a Public Defense Delivery System, the widely recognized indigent defense fundamentals developed by the American Bar Association. Those principles identify the practical necessities for a constitutional delivery system: workload limits, prompt assignment of counsel, adequate confidential client meeting space, continuous representation by the same attorney throughout each case, minimum attorney qualifications, adequate training and supervision, regular quality audits, independence from politics, and parity between prosecution and defense counsel resources. The NLADA Report found grave failures in these areas, and 2013 will hopefully see them corrected at a system-wide level, whether through legislation, litigation, or county-based reform.

“The Joke’s on Us”

Among the sometimes apocryphal tales that make up the territorial history of Idaho is the report of a gravestone epitaph left for an innocent man accused of stealing horses: “LYNCHED BY MISTAKE: THE JOKE’S ON US.” The likelihood that there are innocent men and women separated from their families and locked up in Idaho’s prisons is gruesomely high. The probability that some of the innocent were too poor to afford their own attorney is almost a certainty. The occasion of the 50th year since a prisoner’s handwritten petition resulted in the landmark Gideon decision is a solemn opportunity to reflect on whether what the Supreme Court called an “obvious truth”—that “any person haled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided for him”—has been honored in Idaho. Although effective mechanisms for fulfilling Gideon’s command may not always be so obvious, all members of our bar should work this year to ensure that the joke is not on us.

RITCHIE EPPINK is the Legal Director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Idaho.